This article was first published in the INFOFISH International,

By Zacari Edwards

In this article the author, Social Responsibility Director Zacari Edwards from the International Pole and Line Foundation (IPNLF), argues that seafood companies play a key role in addressing social equity challenges by proactively addressing barriers to market access through their policies, purchasing practices and investment into supply chains. In response, he states that companies and consumers must start to accept that the true cost of seafood products is much higher than it currently is, and that a transformative systemic change from a “profit-first” to a “people-first” approach is essential to ensure that small-scale fishers enjoy equity in human rights protections and social benefits.

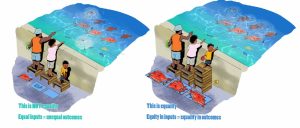

The term social equity is increasingly used throughout the seafood industry but what does it mean, and why is it so important to address? Social equity is often incorrectly used interchangeably with the term social equality, but where social equality is concerned with ensuring groups receive the equal treatment, opportunities and resources; social equity is concerned with accounting for existing inequalities and power relations that have historically hindered vulnerable groups, and ensuring benefits are fairly re-distributed across different groups in society [1]. In other words, social equity looks for interventions that help disrupt the status quo and ensure vulnerable groups receive a fairer share of the resources. This may require unequal interventions that serve to remove disadvantages and, in the end, result in greater equality across societal groups (see Figure 1).

Image 1- Equality vs equity graphic for fisheries practitioners . Image © Sangeeta Mangubhai/WCS & Tui Ledua

There is a growing recognition that access to resources, decision-making processes, and economic benefits are distributed inequitably across various ocean sectors, which have resulted in calls to prioritise social equity [2] . However, throughout the seafood industry there is widespread misunderstanding of the term ‘social equity’, and misalignment in defining what the key social equity challenges actually are. Both represent a significant barrier to advancing social equity in the industry because: “unless greater attention is given to advancing social sustainability and equity, future blue growth will simply perpetuate past social inequalities and harms”[3].

For those that have been working with small-scale fishing communities in the seafood sector, the ingrained social equity challenges we face are clear. Whilst small-scale fisheries are essential for supporting the livelihoods of approximately 379 million people, providing 40% of the global catch and 90% of the total employment in the sector, small-scale fishers receive  the smallest economic benefit in terms of the amount of money they earn for their products [4]

the smallest economic benefit in terms of the amount of money they earn for their products [4]

The growth of industrial fishing activities is amplifying this issue by undermining the livelihoods and food security of small-scale fisheries across the globe, and the increased industrialisation of seafood has contributed to a downward pressure on prices which makes it harder for smaller-scale producers to compete.

At the heart of social equity issues is the broken economics of the seafood sector. With global demand for seafood on the rise, supply of seafood limited, fish stock degradation, and costs rising to catch the same or less quantity of fish, intuitively basic economics says prices must rise too. Yet, with staple seafood products such as tuna, not only have prices not risen, they are subjected to market pressures that drive prices down. So, what’s going on?

To meet the rising consumer demand for cheap seafood, retailers are under pressure to procure seafood at lower prices. Retailers can leverage their position in the supply chain to have their suppliers compete against each other to sell at lower prices, and suppliers will often refrain from asking for the true costs of products as they know their customers will refuse to pay when there are cheaper alternatives available [5] . When it comes to suppliers sourcing from small-scale fisheries, they have the added pressure of competing with industrial fisheries that receive subsidies from governments to keep their fishing operations running above cost. All of this contributes to false price ceilings and ultimately a race to the bottom in terms of the prices being paid for seafood [6] .

A key issue from a social equity and human rights perspective is that “command for low prices not only breeds cheap, flexible and casual labour in food production; it also creates the conditions of insecurity under which forced labour flourishes” [7] . The way the seafood sector’s economy functions has created an unequal distribution of economic benefits that sees harvesters take a smaller share than any other supply chain actor. The inescapable truth is that this need to meet demand for cheap seafood, and the practice of selling seafood around the margins of the cost of production, creates an environment that breeds exploitative practices. To put it more simply, “as the appetite for cheap fish worldwide grows, so does the demand for men who are paid little or nothing to catch it” [8].

The seafood sector has also championed interventions with high financial costs such as eco-certifications and social audits as a means for attaining market entry. These interventions present a significant barrier for small-scale fisheries to enter high value markets [9] ; and are better suited to large-scale fishing operations, that have better access to private finance and greater financial resources to invest into such schemes. This type of inequality playing out in the seafood sector represents a systemic economic failure, and must be redressed to ensure small-scale fisheries receive their fair share of socioeconomic benefits and transition towards a just industry that protects the most vulnerable in society.

At worst, the broken economics of the seafood sector underpin human rights abuses, labour abuses and the poor working conditions faced by fishers on vessels, particularly those from more vulnerable populations. So the problem we face is how to address social equity and human rights challenges in the face of these market dynamics? What systemic change is required to allow for a fairer distribution of human rights protections and social benefits to small-scale fishers? And finally, when margins are this thin for seafood, what socio-economic benefits are we re-distributing and where are these being taken from?

Human rights and labour rights issues in the seafood sector are well-documented and, since the initial exposé of human rights abuses in the Thai seafood sector almost a decade ago [10], our industry has moved on; now, understanding such issues can and do pervade seafood supply chains all over the world. Whilst the seafood sector is rightly concerned with addressing human rights and labour risks in supply chains, what is often left unrecognised is the acute relationship between improving social equity and the protection of human rights.

Inequity which greatly restricts financial opportunities for vulnerable groups can result in a loss of livelihoods altogether [11]. An often overlooked fact is that ensuring sustained market access for small-scale fishers is essential in protecting their human rights that are impacted by insufficient pay and livelihood insecurity. These include their right to life and physical integrity, right to an adequate standard of living, right to adequate food and nutrition, and right to work and rights at work [12]. Businesses therefore play a key role in addressing social equity challenges by proactively addressing barriers to market access through their policies, purchasing practices and investment into supply chains.

Procurement policies set the internal requirements of what type of seafood a company can purchase, and many retailers are often unable to procure seafood from small-scale fisheries as a result of the content of their procurement policies [13]. However, these policies are also somewhat fluid and can be subject to change depending on business priorities, or how companies want to position themselves on environmental and social issues. Applying a social equity lens when formulating procurement policies would help companies understand that market access can act as a key mechanism that helps protect particular human rights, and also understand how to best avoid having an adverse impact on the following human rights related to poverty, livelihood security and income generation [14] :

As individuals lose their economic independence and experience increased levels of poverty, they have fewer possibilities of finding security and protection. By ensuring that procurement policies maintain a level of sourcing from small-scale fisheries, companies can protect fishers’ ability to, at minimum, afford basic necessities such as essential food, shelter, housing, safe drinking water, sanitation etc.

By connecting fishers to higher value markets, companies remove economic barriers faced by small-scale fishers and contribute to productive livelihood activities. High value markets are also subject to more scrutiny in terms of improving their environmental and social performance. This may lead to increased private investment in fishery improvements that help fishers grow their assets, skills and capabilities.

Small-scale fisheries connected to high value markets typically strike a better balance between selling products for export and supporting the food security of their local communities [15,16]. Fishers can also subsidise their household food expenditure through directly consuming less commercially viable catch from their fishing trips [17]. Companies that support such fisheries through their sourcing activities help ensure that they can maximise their income from fishing activities whilst food security benefits are still distributed equitably amongst coastal communities.

Through working with small-scale fisheries, companies help create commercial leverage that can see stakeholders take positive measures to identify, address, and prevent labour issues in their supply chains. In general, access to higher value markets connects small-scale fisheries to various voluntary market initiatives designed to progress the social responsibility performance of supply chains, implement human rights due diligence processes, and/or move fisheries towards the decent work agenda of the International Labor Organisation (ILO). Market access therefore acts as a catalyst in many respects that helps integrate small-scale fisheries in such processes, as well as helping channel resources into small-scale fishery supply chains as required to address issues. However such market-led approaches are not without their citritics, and more can certainly be done in terms of applying social equity to industry processes to advance the benefits for small-scale fishers.

As well as a responsibility to respect human rights in their operations, businesses also have a responsibility to deal with such impacts when they occur [18]. However, in practice, businesses can be more focused on the former rather than the latter.

Human rights and labour rights groups have claimed too many businesses are preoccupied with managing their own reputational risk over protecting the rights of the workers in the supply chains that they source from, but have also encouraged businesses to preferentially source from suppliers with better practices in place as a means of incentivising positive change [19,20]. For small-scale fisheries operating in developing countries, this can create an inherent bias. For example, supply chains could have a higher perceived risk due to insufficient national legislation being in place, or national level risk reports such as the Trafficking in Persons (TIP) country reports, both of which may not reflect the practices at the fishery level, and are ultimately out of the control of small-scale fisheries stakeholders to address.

These dynamics can lead to companies ending business relationships with seafood supply chains and/or small-scale fisheries where there is a higher perceived risk. This approach is problematic from a social equity perspective as it takes away the responsibility of powerful actors to invest in solutions in supply chains, as they can instead simply cherry pick where they buy from and leave supply chains that do not fit their requirements. This type of private sector practice therefore can inadvertently introduce further barriers to small-scale fisheries, and reduce the necessary investment into small-scale fisheries that is required to ensure the longterm realisation of a series of human rights [21].

Overall, companies in the seafood sector are being increasingly criticised for being insufficiently committed to upholding human rights and improving social conditions for workers [22]. The seafood sector has further challenges stemming from a lack of dialogue with human rights and labour groups, and has been criticised for championing ineffective approaches and for its over-reliance on market-based solutions [23]. A key social equity issue faced by small-scale fisheries in this regard is that many voluntary approaches to addressing social issues incur greater costs and logistical requirements as they are designed with industrial fisheries in mind. At present, the CSR activities of seafood companies are ultimately focused on ‘‘doing less harm’’, and at best, ‘‘doing no harm” to workers in their supply chains. To advance social equity, we need a shift in mindset towards “doing more good”, and investing in smallscale fishing communities beyond introducing safeguards towards enabling individuals to thrive and improve their quality of life [24].

To avoid perpetuating existing inequalities further, the seafood sector needs to shift towards mainstreaming social equity issues. We need a transformative approach where the status quo of industry operations is challenged. In this sense, securing, safeguarding and building opportunities for small-scale fisheries to participate in highly competitive global seafood markets is essential for advancing social equity. However, current efforts to address social responsibility and human rights issues in fisheries operate in parallel, or at worst are juxtaposed, to efforts to advance social equity. What we need instead, is a transformative systemic change across the sector to ensure social equity and human rights challenges are addressed in synchronicity.

To advance social equity and human rights in small-scale fisheries, companies must first recognise that their procurement practices can have adverse harmful effects on fishers, and then take steps to remedy this. It is important that companies stop the practice of ending business relationships as an alternative to investing in supply chain improvements, and instead, adopt a risk-based approach that principally looks to remove prohibitive barriers to market access for small-scale fisheries and safeguard the livelihoods of fishers as a result. Companies can do this by including small-scale fishery sourcing requirements in their procurement policies, establishing long-term business partnerships with small-scale fisheries, and investing into supply chains to improve the social safeguards that are in place. Furthermore, companies also need to end the practice of applying downward pressure to ensure they receive lower prices, in recognition of the long-term effect between buying low-priced seafood and perpetuating human rights and labour rights issues. Instead, companies should align their pricing with the levels required to ensure decent working conditions are made possible for workers down the supply chain.

To achieve this, the industry needs to shift its thinking from a “profit-first” economic approach towards a “people first” approach that is centred around improving human wellbeing and quality of life of fishers [25]. As such, companies and consumers must start to accept the true cost of seafood products. To date, the true cost of fish has been much higher than consumers and businesses have had to pay, creating a downward pressure eroding fishers’ pay, working conditions, and at worst, human rights [26,27]. This situation needs to be reversed where increased demand for seafood sold at its true cost creates a “race to the top ‘’ that sees companies make positive investments into supply chains, and take steps to source seafood in a manner that best helps advance social equity and protects human rights. Such a move would also align with changing consumer expectations, and create supply chains that are fit for the future, with younger generations of consumers increasingly demanding socially responsible products and who are willing to pay more for such products as a result [28].

Finally, companies need to ensure that any price premiums paid for responsible seafood products translate to increased pay for fishers rather than being absorbed by other supply chain actors. This can be achieved when companies increase their attention on understanding how wealth is extracted and distributed across different fisheries and see equitable distribution of pay as a key performance criterion when making procurement decisions. Ultimately, much more must be done to financially reward fishers catching more responsible products and ensure that premium payments reach fishers. By improving pricing and/or profit-sharing schemes that generate higher incomes for fishers, companies will help protect human rights, advance social equity and secure a future for coastal fishing communities, ensuring no one is left behind [29].

[1] Guy, M. E., & McCandless, S. A. (2012). Social equity: Its legacy, its promise. Public Administration Review, 72(s1), S5-S13. [2] Osterblum, H., Wabnitz, C. C., Tladi, D., Allison, E., Arnaud-Haond, S., Bebbington, J., ... & Selim, S. A. (2020). Towards ocean equity. [3] Bennett, N. J., Villasante, S., Espinosa-Romero, M. J., Lopes, P. F., Selim, S. A., & Allison, E. H. (2022). Social sustainability and equity in the blue economy. One Earth, 5(9), 964-968. [4] FAO (2022) The contributions of small-scale fisheries to sustainable development [5,6] Duong, T. T. (2018). The true cost of cheap seafood: An analysis of environmental and human exploitation in the seafood industry. Hastings Envt'l LJ, 24, 279. [7] ILRF (2018) Taking Stock: Labor Exploitation, Illegal Fishing and Brand Responsibility in the Seafood Industry [8] Robin McDowell, Margie Mason & Martha Mendoza, AP Tracks Slave Boats to. Papua New Guinea, ASSOCIATED PRESS [9] Pita, C., Ford, A. (2023). Sustainable seafood and small-scale fisheries: improving retail procurement. IIED, London [10] EJF (2015) THAILAND'S SEAFOOD SLAVES. Human Trafficking, Slavery and Murder in Kantang’s Fishing Industry. [11] Osterblum, H., Wabnitz, C. C., Tladi, D., Allison, E., Arnaud-Haond, S., Bebbington, J., ... & Selim, S. A. (2020). Towards ocean equity. [12] DIHR (2021) Enhancing Accountability for Small-Scale Fishers [13] Pita, C., Ford, A. (2023). Sustainable seafood and small-scale fisheries: improving retail procurement. IIED, London [14] OHCHR (2012) Guiding Principles on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights [15] Miller AM, (2017) Social Benefits of one-by-one tuna fisheries, International Pole & Line Foundation [16] Edwards, Z., Sinan, H., Adam, M. S., & Miller, A. (2020). State-led fisheries development: enabling access to resources and markets in the Maldives pole-and-line skipjack tuna fishery. [17] IPNLF (2022) Capturing the socio-economic benefits of handline and pole-andline tuna fisheries in Indonesia [18] United Nations (2011) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework [19] ILRF (2018) Taking Stock: Labor Exploitation, Illegal Fishing and Brand Responsibility in the Seafood Industry [20] Sparks, J. L. D., Matthews, L., Cárdenas, D., & Williams, C. (2022). Worker-less social responsibility: How the proliferation of voluntary labour governance tools in seafood marginalise the workers they claim to protect. Marine Policy, 139, 105044. [21] DIHR (2021) Enhancing Accountability for Small-Scale Fishers [22] Sparks, J. L. D., Matthews, L., Cárdenas, D., & Williams, C. (2022). Worker-less social responsibility: How the proliferation of voluntary labour governance tools in seafood marginalise the workers they claim to protect. Marine Policy, 139, 105044. [23] Edwards (2022) How can we work differently to protect fishers and their human rights in the seafood industry? [24,25] Bennett, N. J., Villasante, S., Espinosa-Romero, M. J., Lopes, P. F., Selim, S. A., & Allison, E. H. (2022). Social sustainability and equity in the blue economy. One Earth, 5(9), 964-968. [26] Duong, T. T. (2018). The true cost of cheap seafood: An analysis of environmental and human exploitation in the seafood industry. Hastings Envt'l LJ, 24, 279. [27] ILRF (2018) Taking Stock: Labor Exploitation, Illegal Fishing and Brand Responsibility in the Seafood Industry [28] Del Giudice, T, Stranieri, S, Caracciolo, F, Ricci, EC, Cembalo, L, Banterle, A and Cicia, G (2018) Corporate Social Responsibility certifications influence consumer preferences and seafood market price. [29] Teh, L. C., Caddell, R., Allison, E. H., Finkbeiner, E. M., Kittinger, J. N., Nakamura, K., & Ota, Y. (2019). The role of human rights in implementing socially responsible seafood. PloS one, 14(1), e0210241.